For many years, I've noticed that it seems like pastors have an inordinate number of special needs children; kids with Down's Syndrome in particular. Of course when we observe something like that, we try to make sense of it in whatever our own worldview might be.

My worldview told me back then that the reason pastors had more kids with developmental disorders was because God knew those kids would need someone special to look after them. Of course, there are a few theological problems with this, but none so serious that they overcome a worldview.

Then, not so long ago, a bit of reality hit me. It has no less theological significance than my older view, and maybe more. It is tragically so much more simple than I originally thought: The reasons pastors seem to have more kids with special needs is, they are members of a group who won't choose to kill those kids in utero when they find out they are sick.

Yes, I know that sounds crass, but I really think it is a better explanation of the observed phenomenon. And it begs a couple questions. First, why only pastors? Why don't believers in general have more kids with special needs than the secular, non-religious culture, especially considering that having those kids means what it means? I read recently that 95% of all Down's Syndrome pregnancies end in abortion now. This can only mean one of two things...either God isn't giving believers kids with special needs, or believers (since there is far more than 5% of the population who are believers) are aborting these kids at a rate similar to secular society.

Now certainly my observations do not a law make. Just because I've seen this doesn't make it reality; I am well aware that conjectural and anecdotal evidence are quite a distance from real empirical science. But the numbers don't lie. Something is up, something more than the simple tragedy of abortion. No wonder Christians can't stop it, if they are some of the ones practicing it.

Showing posts with label theology. Show all posts

Showing posts with label theology. Show all posts

05 March 2013

17 December 2012

The Problem With Works-Based Salvation, in Simple Terms

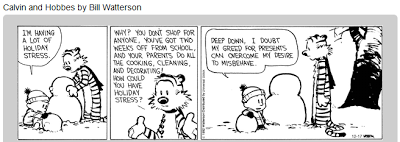

I think today's Calvin and Hobbes cartoon illustrates a great deal of what Martin Luther was trying to say in his Heidelberg Disputation, but says it in a lot simpler terms.

If you want the longer version, I highly recommend two books. The first is the classic by Gerhard Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross. The second is Alistair McGrath's look at the same material, Luther's Theology of the Cross.

I'm planning to re-read Forde's book, as it is one that can't be absorbed fully on the first (or likely the second or third) reading.

I'm working on McGrath's book now. Good stuff. But Calvin (the kid, not the theologian) says it pretty well above.

If you want the longer version, I highly recommend two books. The first is the classic by Gerhard Forde, On Being a Theologian of the Cross. The second is Alistair McGrath's look at the same material, Luther's Theology of the Cross.

I'm planning to re-read Forde's book, as it is one that can't be absorbed fully on the first (or likely the second or third) reading.

I'm working on McGrath's book now. Good stuff. But Calvin (the kid, not the theologian) says it pretty well above.

17 November 2011

"God Won't Give You More Than You Can Handle" Really?

This post from Michael Kelley was too good not to pass on.

14 November 2011

A Thought for the Day

"The issue for Christians is not whether we are going to be theologians but whether we are going to be good theologians or bad ones." -R. C. Sproul, from Knowing Scripture.

10 October 2011

Not Creative, But Faithful

I love this paragraph from Michael Horton's The Gospel Commission:

Sometimes I think one of the biggest problems of evangelicalism in our culture is our own emphasis on individuality that leads us to all kinds of creative ways of expressing what we think the Bible teaches. The problem with this is, we are fallen creatures and what we think the Bible teaches is more often than not flawed. If we ignore the faithful witness of church history (and who even cares about church history anymore...we can't even respect a hymn if it was written more than sixty days ago!), we are not only prone, but defaulted, to err in our creativity.

We, as witnesses to Christ's kingdom, are not called to be creative, but faithful. We absolutely cannot be faithful unless we are saturated in the Word (scripture) and diligent in the study of our history of thought. Those who ignore their theological history are doomed to (heretically) repeat it.

We must never take Christ's work for granted. The gospel is not merely something we take to unbelievers; it is the Word that created and continues to sustain the whole church in its earthly pilgrimage. In addition, we must never confuse Christ's work with our own. There is a lot of loose talk these days about our "living the gospel" or even "being the gospel," as if our lives were the Good News. We even hear it said that the church is an extension of Christ's incarnation and redeeming work, as if Jesus came to provide the moral example or template and we are called to complete his work. But there is one Savior and one head of the church. To him alone all authority is given in heaven and on earth. There is only one incarnation of God in history, and he finished the work of fulfilling all righteousness, bearing the curse, and triumphing over sin and death.

Sometimes I think one of the biggest problems of evangelicalism in our culture is our own emphasis on individuality that leads us to all kinds of creative ways of expressing what we think the Bible teaches. The problem with this is, we are fallen creatures and what we think the Bible teaches is more often than not flawed. If we ignore the faithful witness of church history (and who even cares about church history anymore...we can't even respect a hymn if it was written more than sixty days ago!), we are not only prone, but defaulted, to err in our creativity.

We, as witnesses to Christ's kingdom, are not called to be creative, but faithful. We absolutely cannot be faithful unless we are saturated in the Word (scripture) and diligent in the study of our history of thought. Those who ignore their theological history are doomed to (heretically) repeat it.

09 October 2011

Finally, A Reformed Theolgian Speaks in the Panhandle

I had what I consider the privilege to hear Dr. Carl Trueman give four lectures on Martin Luther this weekend in Amarillo. Dr. Trueman is the Academic Dean and Professor of History and Historical Theology at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia.

Dr. Trueman is a gifted story-teller and fascinating speaker. We rarely get this caliber of reformed speaker here. The Texas Panhandle is the heart of arminian theology (hey, TX is the state that produced Joel Osteen...to our shame). There aren't any reformed seminaries in this area, and the only ones I know of down-state are extensions of bigger seminaries. So it is a rare treat to have someone of Dr. Trueman's ability here.

Funny anecdote: I gave Dr. Trueman one of my Wayland pens I had printed up with Luther's slogan, simul iustus et peccator. He seemed to like it and told me it would end up on his, 'Luther artifacts' shelf in his office. I find that funny, in a good sort of way.

He has all the skills necessary to become a 'celebrity pastor'. I don't think he'll be pursuing that pedigree, though.

Dr. Trueman is a gifted story-teller and fascinating speaker. We rarely get this caliber of reformed speaker here. The Texas Panhandle is the heart of arminian theology (hey, TX is the state that produced Joel Osteen...to our shame). There aren't any reformed seminaries in this area, and the only ones I know of down-state are extensions of bigger seminaries. So it is a rare treat to have someone of Dr. Trueman's ability here.

Funny anecdote: I gave Dr. Trueman one of my Wayland pens I had printed up with Luther's slogan, simul iustus et peccator. He seemed to like it and told me it would end up on his, 'Luther artifacts' shelf in his office. I find that funny, in a good sort of way.

He has all the skills necessary to become a 'celebrity pastor'. I don't think he'll be pursuing that pedigree, though.

06 October 2011

A Funny Feeling

Why do I get the funny feeling that the level and depth of theology in this book-

is no different than what's found in this video, which may or may not be of similar title by coincidence?

is no different than what's found in this video, which may or may not be of similar title by coincidence?

08 August 2011

Why Theology Shouldn't Be, and Can't Be, Boring

Carl Trueman posted this blog entry on why we must fire boring teachers and preachers (taken from his recent sermon on 1 Timothy 1).

Now, I'm a Sunday School teacher. Something like this can be threatening to someone like me. Yet it is important that I not run away from the threat.

I fear that I often vacillate between the two extremes- being interesting without saying much, and saying a lot, dryly. The first I'll call the Obama effect. He is a very interesting speaker, but when you listen to the words, he doesn't say much. (But then, most politicians don't...that's not necessarily a personal problem for the President.) The second I'll call the Pinhead position. Most pinheads (dry academic types) really do know their stuff, but they make everyone with whom they come in contact very uninterested in their stuff by the way they present it.

There's a third way- I'll call it the Reagan method (sorry, no clever alliteration there...suggestions welcome). Ronald Reagan could say a great deal of meaningful things in a most concise and efficient manner, and do it in an engaging and fascinating manner. He wasn't called, The Great Communicator for no reason. That's how I need to do what I do on Sunday mornings, and if Trueman is right, that's how our pastors should be doing what they do.

But let's not get Descartes before the horse*. I'm not suggestion that I (or your pastor) come up with a false method of engaging the respective audience for the purpose of being interesting. And that's not Trueman's point either. The point is, doctrine (what the scripture is telling us about God) should be engaging and interesting by its very nature. Here's how Trueman puts it in his blog-

"...making providence...as dull as ditch water is false teaching as sure as open theism is."

I've been trying to establish the principle for a couple months in our SS class this summer. We've taken a short break from our expositional book study to look at some theology. Specifically, we are looking at the attributes of God, both communicable and incommunicable, trying to get a better understanding of God's nature and character. I keep telling my folks that this is a worthwhile endeavor, and is God-honoring. I think most of them agree, but a few have dropped off the map the last couple weeks. I don't know if it is due to last-moment-summer-vacation-before-school-starts, or the sometimes dryness of the topic. You see, I'm not John Piper, and I can stumble over this material and not communicate the passion I have for it if I'm not careful. That's unfortunate, because this can tend to make the material less engaging to the average SS student.

I continue to pray that all of us would find the character and nature of God a thing that fascinates us. Because if it bores us, we need a serious (as it were) check-up from the neck-up.

____________

[rimshot]

Now, I'm a Sunday School teacher. Something like this can be threatening to someone like me. Yet it is important that I not run away from the threat.

I fear that I often vacillate between the two extremes- being interesting without saying much, and saying a lot, dryly. The first I'll call the Obama effect. He is a very interesting speaker, but when you listen to the words, he doesn't say much. (But then, most politicians don't...that's not necessarily a personal problem for the President.) The second I'll call the Pinhead position. Most pinheads (dry academic types) really do know their stuff, but they make everyone with whom they come in contact very uninterested in their stuff by the way they present it.

There's a third way- I'll call it the Reagan method (sorry, no clever alliteration there...suggestions welcome). Ronald Reagan could say a great deal of meaningful things in a most concise and efficient manner, and do it in an engaging and fascinating manner. He wasn't called, The Great Communicator for no reason. That's how I need to do what I do on Sunday mornings, and if Trueman is right, that's how our pastors should be doing what they do.

But let's not get Descartes before the horse*. I'm not suggestion that I (or your pastor) come up with a false method of engaging the respective audience for the purpose of being interesting. And that's not Trueman's point either. The point is, doctrine (what the scripture is telling us about God) should be engaging and interesting by its very nature. Here's how Trueman puts it in his blog-

"...making providence...as dull as ditch water is false teaching as sure as open theism is."

I've been trying to establish the principle for a couple months in our SS class this summer. We've taken a short break from our expositional book study to look at some theology. Specifically, we are looking at the attributes of God, both communicable and incommunicable, trying to get a better understanding of God's nature and character. I keep telling my folks that this is a worthwhile endeavor, and is God-honoring. I think most of them agree, but a few have dropped off the map the last couple weeks. I don't know if it is due to last-moment-summer-vacation-before-school-starts, or the sometimes dryness of the topic. You see, I'm not John Piper, and I can stumble over this material and not communicate the passion I have for it if I'm not careful. That's unfortunate, because this can tend to make the material less engaging to the average SS student.

I continue to pray that all of us would find the character and nature of God a thing that fascinates us. Because if it bores us, we need a serious (as it were) check-up from the neck-up.

____________

* For those of you who didn't take a philosophy class, his name is pronounced, "Day-cart". My mixed metaphor comes from this old joke-

One day a man wandered in to his veterinarian's office and asked about having his horse put down.

"Why," asked the vet.

"Well, he won't pull my milk cart any more."

"How's that?", asked the vet.

"He's an unusual horse," the milkman explained. "He loves to read philosophy. Instead of dangling a carrot from a stick to make him go, I'd just tie a book by Thales or Hume or Sartre on the stick and he'd follow wherever I lead. But now, he wont' move."

"Let's take a look," said the vet. Upon examining the setup, the vet said, "I think I've found the problem."

"What is it?" asked the milkman.

"You've got Descartes before the horse," explained the vet.

29 July 2011

How Could God Ask Abraham to Sacrifice His Son?

I've heard this one thrown around a lot of different ways, and most often as a criticism of God and His character.

Nancy Guthrie has a very good post on the Gospel Coalition blog today- "How Could God Ask That?"

Here's a quote- "Why would God ask Abraham to offer his son as a sacrifice? Is God trying to teach us that we should be willing sacrifice what is most precious to us? No. This story is not recorded to inspire sacrifice to God. Instead, it paints in vivid colors the sacrifice of God. The point of this story is not to convince you that you must be willing to sacrifice to God what is most precious to you, but rather to prepare you to take in the magnitude of the gift when you see that God was willing to sacrifice what was most precious to him—his own beloved Son—for you."

Kinda changes the perspective, no?

Nancy Guthrie has a very good post on the Gospel Coalition blog today- "How Could God Ask That?"

Here's a quote- "Why would God ask Abraham to offer his son as a sacrifice? Is God trying to teach us that we should be willing sacrifice what is most precious to us? No. This story is not recorded to inspire sacrifice to God. Instead, it paints in vivid colors the sacrifice of God. The point of this story is not to convince you that you must be willing to sacrifice to God what is most precious to you, but rather to prepare you to take in the magnitude of the gift when you see that God was willing to sacrifice what was most precious to him—his own beloved Son—for you."

Kinda changes the perspective, no?

05 May 2011

What We Need (Obscure Lectures)

I just ran across a set of three talks given by Sinclair Ferguson at a Desiring God conference way back in 1990. It was on universalism, by the way, which is a hot topic right now...probably a lot hotter than it was in 1990. There was no way to know about these talks other than finding them by chance.

What we need- a web site that lists links to all these 'lost' talks by good folks like Dr. Ferguson, and like Carson/Dever/Piper/Sproul/Chandler/Keller/Tchividjian/Horton/Ortlund/and-so-on. I almost never get to hear any of these things live, and can usually only find stuff if it's on a particular person's (or his ministry's) web site. These talks that get put in obscure places are effectively lost except to those who put them there.

Any of you who read this blog (not many, I know!) and can get the word out to the YRR blogger types please do so. I'd love to have a way to access these hard-to-find talks, sermons, and conference messages. These messages are too valuable to lose in the vast expanses of the internet.

What we need- a web site that lists links to all these 'lost' talks by good folks like Dr. Ferguson, and like Carson/Dever/Piper/Sproul/Chandler/Keller/Tchividjian/Horton/Ortlund/and-so-on. I almost never get to hear any of these things live, and can usually only find stuff if it's on a particular person's (or his ministry's) web site. These talks that get put in obscure places are effectively lost except to those who put them there.

Any of you who read this blog (not many, I know!) and can get the word out to the YRR blogger types please do so. I'd love to have a way to access these hard-to-find talks, sermons, and conference messages. These messages are too valuable to lose in the vast expanses of the internet.

03 May 2011

We are the Friend of God, but God is Not Our Friend...Huh?

I ran across a line in D. A. Carson's book, The Difficult Doctrine of the Love of God last night that really made me think. Carson says, "No where in scripture is God or Jesus ever spoken of as our friend."

Now, I immediately had the same reaction you might have when you read the title of my blog post. You remember, just as I did, that scripture talks about us being friends, right? Well, go re-read that passage (James 2:23 if you've misplaced it). It talks about us being the friend of God...but not the other way around. How is that possible?

Carson uses this illustration, which I've edited a bit for clarity. He uses the illustration of a military officer and an enlisted man. In one case, the officer has known the man's family for years and watched him grow up. He says, "Jim, go get the Hummer. I need you to drive me to a meeting at HQ. While I'm in the meeting, you can use the Hummer to run around or go catch a movie. Just be back to pick me up at 1600." No problem then, if the enlisted man goes to a movie in the Colonel's Hummer.

In the other case, the two are not acquainted. The Colonel says, "Corporal, go get the Hummer. I need you to drive me to the HQ for a meeting. I'll be finished at 1600."

The corporal then responds, "Only on one condition, sir. I want to take the Hummer and catch a movie. It'll be over by 1630...just wait for me and I'll pick you up when I'm done." Problem? I'd say three-hots-and-a-cot is in store for the corporal.

Do you see the difference between the corporal being a friend of the Colonel, and the Colonel being a friend of the corporal?

Why is this relationship with God important? Well, we've managed to screw it up pretty royally in our churches today, and this sermon jam from Richard Ganz is a pretty good illustration of why it's a problem.

This is another reason why you (who know me) hear me rail against Jesus-is-my-boyfriend music...it is a theological distortion of significant proportion. I love the line from The Voice's song, WDJD- "...Jesus is not your homeboy, your dog; he is God and will bite you, hard and right through...".

Click that link and download the song and listen to it...there's more depth in it than any hundred Jesus-prom-songs combined. And get Carson's book. It only takes about an hour to read the whole thing. It's an hour well-spent.

Now, I immediately had the same reaction you might have when you read the title of my blog post. You remember, just as I did, that scripture talks about us being friends, right? Well, go re-read that passage (James 2:23 if you've misplaced it). It talks about us being the friend of God...but not the other way around. How is that possible?

Carson uses this illustration, which I've edited a bit for clarity. He uses the illustration of a military officer and an enlisted man. In one case, the officer has known the man's family for years and watched him grow up. He says, "Jim, go get the Hummer. I need you to drive me to a meeting at HQ. While I'm in the meeting, you can use the Hummer to run around or go catch a movie. Just be back to pick me up at 1600." No problem then, if the enlisted man goes to a movie in the Colonel's Hummer.

In the other case, the two are not acquainted. The Colonel says, "Corporal, go get the Hummer. I need you to drive me to the HQ for a meeting. I'll be finished at 1600."

The corporal then responds, "Only on one condition, sir. I want to take the Hummer and catch a movie. It'll be over by 1630...just wait for me and I'll pick you up when I'm done." Problem? I'd say three-hots-and-a-cot is in store for the corporal.

Do you see the difference between the corporal being a friend of the Colonel, and the Colonel being a friend of the corporal?

Why is this relationship with God important? Well, we've managed to screw it up pretty royally in our churches today, and this sermon jam from Richard Ganz is a pretty good illustration of why it's a problem.

This is another reason why you (who know me) hear me rail against Jesus-is-my-boyfriend music...it is a theological distortion of significant proportion. I love the line from The Voice's song, WDJD- "...Jesus is not your homeboy, your dog; he is God and will bite you, hard and right through...".

Click that link and download the song and listen to it...there's more depth in it than any hundred Jesus-prom-songs combined. And get Carson's book. It only takes about an hour to read the whole thing. It's an hour well-spent.

02 May 2011

A Couple Worth Repeating

I noted a couple of excellent blog posts this weekend, and I'll pass them along.

If you are worried you might be addicted to Facebook, Twitter, et al., this blog from Tim Challies is a must-read (it's worth a read even if you aren't addicted).

Then, this post from Trevin Wax on Humility and Humor was just outstanding. If you only read one blog a day, read Challies'. If you read two, read Challies' and Wax's. (Of course, you can always read mine as well!)

Of course, if you read Challies, you've already seen the next one. But if not, it is worth looking at.

This is an article on why Genesis 1 and 2 are not poetry, but historical narrative. (Yes, this is important.)

Good reading!

If you are worried you might be addicted to Facebook, Twitter, et al., this blog from Tim Challies is a must-read (it's worth a read even if you aren't addicted).

Then, this post from Trevin Wax on Humility and Humor was just outstanding. If you only read one blog a day, read Challies'. If you read two, read Challies' and Wax's. (Of course, you can always read mine as well!)

Of course, if you read Challies, you've already seen the next one. But if not, it is worth looking at.

This is an article on why Genesis 1 and 2 are not poetry, but historical narrative. (Yes, this is important.)

Good reading!

28 April 2011

The Doctrine of Election

I was challenged today with the statement below. For clarity, I posted the entire statement, then responded to it (with his comments in yellow) underneath.

Here's the original statement-

Here is how I responded-

"" ..."choosing" some, and not choosing others. Where's the grace in that?"

I guess it all depends on how you define, 'grace'. Since grace is, 'unmerited favor', I can't see a problem with Him choosing some and not others. Eph. 1:4-6 makes this pretty clear, and it gives us the reason..."according to the purpose of his will." 2 Tim. 1:9 re-iterates this- "...in virtue of his own purpose and the grace which he gave us in Christ Jesus ages ago."

"we wind up in some positions that I humbly submit put God in a rather awkward stance as well--one that I believe is contrary to his nature."

Can you name or describe some of these positions?

"If God solely predestines some of us to not be saved, what was his purpose in creating us?"

For his sovereign good pleasure and for his glory. You didn't think the story about Pharoah was only a historical narrative, did you? Paul didn't...see Romans 9. In reprobation, God doesn't need to predestine anyone to hell...we take care of that on our own. He simply chooses to pass over those he has not chosen for salvation. This is a difficult teaching, and one I am not comfortable with, but I am trusting in both the justice and grace of God. Jude 4 alludes to this doctrine. So do Romans 11:7 and 1 Pet. 2:8. Romans 9:17-22 makes it explicit, but that still doesn't make it easy.

"How could a loving, just God create a being that he knew no matter what that individual did, was already destined for the fires of Hell? "

He couldn't. The problem isn't with the nature of God, or with a particular system of theological interpretation of God, but with the premise of the question. It assumes that some will be sinless, or at least choose God, without his intervention. Jesus said that can't happen. God created ALL OF US knowing we were destined to the fires of hell, not just some of us.

He didn't look down the corridors of time and see which of us would choose him...He looked down the corridors of time and saw that, “None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one.Their throat is an open grave; they use their tongues to deceive. The venom of asps is under their lips. Their mouth is full of curses and bitterness. Their feet are swift to shed blood; in their paths are ruin and misery, and the way of peace they have not known. There is no fear of God before their eyes.”

"if we give NO role to man in accepting that act, then what are we to do?"

Oh, we have a role...we must believe. Really believe. The notitia/assensus/fiducia kind of believe. But we can't even do that without God's intervention (Eph. 2:1-10; John 6:44).

"Free will has to be in here somewhere."

It is. We all have free will (liberium arbitrium), whether saved or lost, and we all choose what we want. The problem lies in what, exactly, we want. What we do not have, if we are unregenerate, is the will to choose God or righteousness (libertas). In other words, as Paul clearly states in Romans 3, and Jesus clearly indicates in John 3:3 and John 6:44 and 6:65, we will never choose God. Scripture never speaks of free will in any other context than God's free will to do what he sovereignly wishes. It clearly states that all of what is necessary for us to seek after God occurs at the hand of God (Ezek. 36:26-7). Acts 16:14 is an example of this, and 1 Cor. 2:14 is an explanation of how it manifests itself in the unregenerate.

"And a God who capriciously extends salvation"

Be careful. Do not blaspheme a holy God who has extended salvation to YOU. It is on the basis of grace that we have been saved, not capriciousness.

"Where do we see a Scriptural basis for God loving some more than others?"

It's a theme found throughout scripture, both the OT and the NT. The clearest picture of it is in Romans 9- "Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated." It is also seen clearly in Deut. 7:7-8, with all the accoutrements that surround that idea. In the old covenant, God had a chosen people that he divinely loved and protected, even though they were just as sinful as the nations surrounding them. In the new covenant, he has the same. Jesus died for the elect (Eph. 5:25, Rom. 8:32-4; Jn. 6:37-9; Jn. 17:9; 2 Cor 5:21, etc.). The fact that there is an elect is logical proof that God loves some in a different way than he loves others.

"both Paul and Peter tell us that God wants all to be saved...how can he want something that he has made impossible? "

You need to clarify who, 'all' means in the context of those verses. Just because the word, 'all' is used does not mean it intends to be a human universal. Can we all agree on that? (humor) Look at Romans 8:32. It says, "..he gave up his son for us all." Then in v. 33, he says who 'all' is- "Who shall bring any charge against God's elect?"

Secondly, you need to make a distinction between the necessary will (Ex. 3:14) and the free will of God. Do you think God 'wanted' evil to exist? Yet he made it possible. This mystery is found to some degree in Acts 2:23, where Peter speaks of the crucifixion as being both, "...according to the definite plan...of God" and, "...crucified and killed at the hands of lawless men." God doesn't will something he makes impossible. Scripture is clear that with man, things are impossible, but with God, anything is possible. Instead, God makes possible something he wills (salvation for a hopelessly lost person, like me).

"Every man has his own free will to choose whether to accept that invitation"

In one sense, this is correct. But in the sense I think you intend, then you have made the will of man sovereign over the will of God. To give man a role in his own salvation is to negate the entire concept of grace. After all, grace is not grace if it is merited. When Jesus said, "Flesh profits nothing," he didn't mean, "a little something." He meant what he said. The only freedom of will we have to accept Christ is the freedom of being regenerate (John 3:3). Without that, we cannot choose to accept it, because we can't even SEE it. If faith brings about regeneration, the faith is a WORK. But if regeneration brings about faith, then what Jesus told Nicodemus makes sense, and what Paul said in Ephesians 2 make sense, and God gets all the glory for our salvation, rather than sharing his glory with another (us).

I hope this is constructive.

How could I have better answered the comments?

.

Here's the original statement-

"I realize I'm going further down a well traveled rabbit trail, and I'm going into a theological gunfight armed with a pen-knife, but I have a real difficulty with an understanding of God as "choosing" some, and not choosing others. Where's the grace in that? Or the justice, for that matter? I have heard the arguments for "grace alone", and I agree that grace initiates, but when we contort ourselves into theological pretzels to ensure that man has NO role in his salvation, we wind up in some positions that I humbly submit put God in a rather awkward stance as well--one that I believe is contrary to his nature.

If God solely predestines some of us to not be saved, what was his purpose in creating us? How could a loving, just God create a being that he knew no matter what that individual did, was already destined for the fires of Hell?

Yes, I affirm that God initiates the offer of salvation, but if we give NO role to man in accepting that act, then what are we to do? How can you be sure of your salvation?

Sorry guys, but I walked this twisted path for a major portion of my life, and I have to disagree. Free will has to be in here somewhere. And a God who capriciously extends salvation only two a limited number, when "ALL have sinned and fallen short" doesn't sound like a very just God to me (let alone merciful).

Where do we see a Scriptural basis for God loving some more than others? If God deliberately does not extend the means (or invitation) to salvation to some, is he confused? Because both Paul and Peter tell us that God wants all to be saved...how can he want something that he has made impossible?

I submit that God extends the opportunity and invitation to salvation to ALL men. Every man has his own free will to choose whether to accept that invitation. The "elect" are those who have (or will in the future) accept that invitation. I believe that to exclude any role for man makes God into something that he is not."

If God solely predestines some of us to not be saved, what was his purpose in creating us? How could a loving, just God create a being that he knew no matter what that individual did, was already destined for the fires of Hell?

Yes, I affirm that God initiates the offer of salvation, but if we give NO role to man in accepting that act, then what are we to do? How can you be sure of your salvation?

Sorry guys, but I walked this twisted path for a major portion of my life, and I have to disagree. Free will has to be in here somewhere. And a God who capriciously extends salvation only two a limited number, when "ALL have sinned and fallen short" doesn't sound like a very just God to me (let alone merciful).

Where do we see a Scriptural basis for God loving some more than others? If God deliberately does not extend the means (or invitation) to salvation to some, is he confused? Because both Paul and Peter tell us that God wants all to be saved...how can he want something that he has made impossible?

I submit that God extends the opportunity and invitation to salvation to ALL men. Every man has his own free will to choose whether to accept that invitation. The "elect" are those who have (or will in the future) accept that invitation. I believe that to exclude any role for man makes God into something that he is not."

Here is how I responded-

"" ..."choosing" some, and not choosing others. Where's the grace in that?"

I guess it all depends on how you define, 'grace'. Since grace is, 'unmerited favor', I can't see a problem with Him choosing some and not others. Eph. 1:4-6 makes this pretty clear, and it gives us the reason..."according to the purpose of his will." 2 Tim. 1:9 re-iterates this- "...in virtue of his own purpose and the grace which he gave us in Christ Jesus ages ago."

"we wind up in some positions that I humbly submit put God in a rather awkward stance as well--one that I believe is contrary to his nature."

Can you name or describe some of these positions?

"If God solely predestines some of us to not be saved, what was his purpose in creating us?"

For his sovereign good pleasure and for his glory. You didn't think the story about Pharoah was only a historical narrative, did you? Paul didn't...see Romans 9. In reprobation, God doesn't need to predestine anyone to hell...we take care of that on our own. He simply chooses to pass over those he has not chosen for salvation. This is a difficult teaching, and one I am not comfortable with, but I am trusting in both the justice and grace of God. Jude 4 alludes to this doctrine. So do Romans 11:7 and 1 Pet. 2:8. Romans 9:17-22 makes it explicit, but that still doesn't make it easy.

"How could a loving, just God create a being that he knew no matter what that individual did, was already destined for the fires of Hell? "

He couldn't. The problem isn't with the nature of God, or with a particular system of theological interpretation of God, but with the premise of the question. It assumes that some will be sinless, or at least choose God, without his intervention. Jesus said that can't happen. God created ALL OF US knowing we were destined to the fires of hell, not just some of us.

He didn't look down the corridors of time and see which of us would choose him...He looked down the corridors of time and saw that, “None is righteous, no, not one; no one understands; no one seeks for God. All have turned aside; together they have become worthless; no one does good, not even one.Their throat is an open grave; they use their tongues to deceive. The venom of asps is under their lips. Their mouth is full of curses and bitterness. Their feet are swift to shed blood; in their paths are ruin and misery, and the way of peace they have not known. There is no fear of God before their eyes.”

"if we give NO role to man in accepting that act, then what are we to do?"

Oh, we have a role...we must believe. Really believe. The notitia/assensus/fiducia kind of believe. But we can't even do that without God's intervention (Eph. 2:1-10; John 6:44).

"Free will has to be in here somewhere."

It is. We all have free will (liberium arbitrium), whether saved or lost, and we all choose what we want. The problem lies in what, exactly, we want. What we do not have, if we are unregenerate, is the will to choose God or righteousness (libertas). In other words, as Paul clearly states in Romans 3, and Jesus clearly indicates in John 3:3 and John 6:44 and 6:65, we will never choose God. Scripture never speaks of free will in any other context than God's free will to do what he sovereignly wishes. It clearly states that all of what is necessary for us to seek after God occurs at the hand of God (Ezek. 36:26-7). Acts 16:14 is an example of this, and 1 Cor. 2:14 is an explanation of how it manifests itself in the unregenerate.

"And a God who capriciously extends salvation"

Be careful. Do not blaspheme a holy God who has extended salvation to YOU. It is on the basis of grace that we have been saved, not capriciousness.

"Where do we see a Scriptural basis for God loving some more than others?"

It's a theme found throughout scripture, both the OT and the NT. The clearest picture of it is in Romans 9- "Jacob I loved, but Esau I hated." It is also seen clearly in Deut. 7:7-8, with all the accoutrements that surround that idea. In the old covenant, God had a chosen people that he divinely loved and protected, even though they were just as sinful as the nations surrounding them. In the new covenant, he has the same. Jesus died for the elect (Eph. 5:25, Rom. 8:32-4; Jn. 6:37-9; Jn. 17:9; 2 Cor 5:21, etc.). The fact that there is an elect is logical proof that God loves some in a different way than he loves others.

"both Paul and Peter tell us that God wants all to be saved...how can he want something that he has made impossible? "

You need to clarify who, 'all' means in the context of those verses. Just because the word, 'all' is used does not mean it intends to be a human universal. Can we all agree on that? (humor) Look at Romans 8:32. It says, "..he gave up his son for us all." Then in v. 33, he says who 'all' is- "Who shall bring any charge against God's elect?"

Secondly, you need to make a distinction between the necessary will (Ex. 3:14) and the free will of God. Do you think God 'wanted' evil to exist? Yet he made it possible. This mystery is found to some degree in Acts 2:23, where Peter speaks of the crucifixion as being both, "...according to the definite plan...of God" and, "...crucified and killed at the hands of lawless men." God doesn't will something he makes impossible. Scripture is clear that with man, things are impossible, but with God, anything is possible. Instead, God makes possible something he wills (salvation for a hopelessly lost person, like me).

"Every man has his own free will to choose whether to accept that invitation"

In one sense, this is correct. But in the sense I think you intend, then you have made the will of man sovereign over the will of God. To give man a role in his own salvation is to negate the entire concept of grace. After all, grace is not grace if it is merited. When Jesus said, "Flesh profits nothing," he didn't mean, "a little something." He meant what he said. The only freedom of will we have to accept Christ is the freedom of being regenerate (John 3:3). Without that, we cannot choose to accept it, because we can't even SEE it. If faith brings about regeneration, the faith is a WORK. But if regeneration brings about faith, then what Jesus told Nicodemus makes sense, and what Paul said in Ephesians 2 make sense, and God gets all the glory for our salvation, rather than sharing his glory with another (us).

I hope this is constructive.

How could I have better answered the comments?

.

25 April 2011

Natural Theology, Aquinas, Augustine, and Muslim Philosophy

As an answer to a discussion question in my Historical Theology class, I posted the following-

As a trained scientist I've paid a bit of attention to this topic. I won't even try to be brief.

--------------------

The Bible simply assumes the existence of God, without making any attempt to prove it. So why should we look outside the Bible for reasons for His existence? Is this attempt trying to lift nature higher than scripture? What is the relationship between nature and grace; reason and faith?

First, we should define 'natural theology'. The simplest definition I know is from RC Sproul- a knowledge of God that is gained from nature.

There are many different views of what natural theology is and means, which explains some of the controversy around the concept. It is based on 'general revelation', but is not the same thing. General revelation refers to something God does, but natural theology is something we do. Natural theology comes out of general revelation.

The audience to general revelation is universal. Not everybody has access to special revelation (at least, not yet).

The content of general revelation is also general, not specific. We can learn general characteristics of God, but not specifics, such as the nature of the trinity, and so forth.

In general revelation, we have two kinds- mediate and immediate general revelation. Mediate is that revelation that God gives to all people through some medium. It is indirect. "The heavens declare the glory of God..." is the psalmist saying that by looking at nature, we see that though the stars are not God, they display some of the glory of their maker. Immediate is the revelation that God gives to all people directly, without an intervening media. Romans tells us that God has written his law on our hearts...this is immediate and directly from God. It is not a deduction from nature. We get this inscription by virtue of being human. Calvin called this the sensus divinitatus.

Natural theology is of course most associated with Thomas Aquinas...as a result, protestants tend to view natural theology as a strictly Roman Catholic process, and thus shy away from it. Francis Schaeffer, for example, claimed that Aquinas separated nature from grace. As much as I like Schaeffer, I don't think he understood Aquinas completely enough to make these distinctions without destroying the union between nature and grace that Aquinas developed.

To understand what Aquinas was trying to do, we need to see him in his context. What problem was Aquinas trying to solve? The answer was Islam. Islam was the greatest threat to the church at this time...and was supported by powerful Muslim philosophers. They argued something called, 'Integral Aristotelianism'. (Say that fast three times!) This was a synthesis between Muslim theology on the one hand and Aristotle on the other. Their central thesis was the 'double-truth' theory. This theory stated that something could be true in philosophy and false in religion at the same time (i.e., true in science, false in theology).

[This sounds remarkably like contemporary arguments for the co-existence of evolution and theism by Biologos, by the way; and is a philosophical stance that I held in my own life for a number of years as a neo-Darwinist before God's grace revealed the falsehood of the idea.]

St. Thomas developed his ideas of natural theology in response to this double-truth theory from Islamic philosophy. He said we can and must distinguish between nature and grace. What he meant was, there are certain things we can learn from nature that we don't learn from special revelation. The bible doesn't teach us anything about nuclear physics, or molecular biology, even though the study of these things is made possible by the common grace of God on man. And while these things are to be distinguished, one cannot be true in one arena and false in the other. This would violate the law of non-contradiction.

Thomas added a third category- the articulus mixtus (mixed articles). These are things that can be learned from either the Bible or from the study of nature. Chief among these things is the existence of God (RE Paul in Romans 1). Thus, the reason the Bible does not argue the existence of God is, from the beginning, God has proven his existence beyond any doubt in nature. So Aquinas argues that the existence of God is proven both by nature and by scripture. He doesn't separate these two things, he makes distinctions.

Thomas stood on Augustine's shoulders. Augustine taught his students that they should learn as much as they could learn about whatever they could, because all truth was God's truth and would reveal God. Augustine's natural theology was based on Paul, of course.

In Rom. 1, Paul goes back to show why the gospel is necessary, and this is based in general revelation. People aren't condemned because of rejecting the Jesus they've never heard of, but because of what they've done with the knowledge of God that they DO have. This 'suppression of the truth of God' is the primary sin of fallen humanity. As Paul says, God has made the truth about himself (that may be known) manifest (phaneros/manifestum); yet we have rejected it.

The general revelation Paul speaks of produces a natural theology in us. This natural theology clearly gives us enough knowledge to condemn us. It does not give enough to save us. For that we need special revelation.

One other point is important: If God reveals himself in nature and in scripture, and the primary textbook of the scientist is nature, and the primary textbook of the theologian is the Bible, why is there conflict between science and theology? Because we live in a fallen world, we don't have complete understanding of either nature or God. Both the scientific community can correct the church (as we probed earlier in the term), and the church can correct the scientific community. But both nature and scripture reveal God, limited as our understanding in both arenas may be.

Reference- Sproul RC. Defending your faith.

As a trained scientist I've paid a bit of attention to this topic. I won't even try to be brief.

--------------------

The Bible simply assumes the existence of God, without making any attempt to prove it. So why should we look outside the Bible for reasons for His existence? Is this attempt trying to lift nature higher than scripture? What is the relationship between nature and grace; reason and faith?

First, we should define 'natural theology'. The simplest definition I know is from RC Sproul- a knowledge of God that is gained from nature.

There are many different views of what natural theology is and means, which explains some of the controversy around the concept. It is based on 'general revelation', but is not the same thing. General revelation refers to something God does, but natural theology is something we do. Natural theology comes out of general revelation.

The audience to general revelation is universal. Not everybody has access to special revelation (at least, not yet).

The content of general revelation is also general, not specific. We can learn general characteristics of God, but not specifics, such as the nature of the trinity, and so forth.

In general revelation, we have two kinds- mediate and immediate general revelation. Mediate is that revelation that God gives to all people through some medium. It is indirect. "The heavens declare the glory of God..." is the psalmist saying that by looking at nature, we see that though the stars are not God, they display some of the glory of their maker. Immediate is the revelation that God gives to all people directly, without an intervening media. Romans tells us that God has written his law on our hearts...this is immediate and directly from God. It is not a deduction from nature. We get this inscription by virtue of being human. Calvin called this the sensus divinitatus.

Natural theology is of course most associated with Thomas Aquinas...as a result, protestants tend to view natural theology as a strictly Roman Catholic process, and thus shy away from it. Francis Schaeffer, for example, claimed that Aquinas separated nature from grace. As much as I like Schaeffer, I don't think he understood Aquinas completely enough to make these distinctions without destroying the union between nature and grace that Aquinas developed.

To understand what Aquinas was trying to do, we need to see him in his context. What problem was Aquinas trying to solve? The answer was Islam. Islam was the greatest threat to the church at this time...and was supported by powerful Muslim philosophers. They argued something called, 'Integral Aristotelianism'. (Say that fast three times!) This was a synthesis between Muslim theology on the one hand and Aristotle on the other. Their central thesis was the 'double-truth' theory. This theory stated that something could be true in philosophy and false in religion at the same time (i.e., true in science, false in theology).

[This sounds remarkably like contemporary arguments for the co-existence of evolution and theism by Biologos, by the way; and is a philosophical stance that I held in my own life for a number of years as a neo-Darwinist before God's grace revealed the falsehood of the idea.]

St. Thomas developed his ideas of natural theology in response to this double-truth theory from Islamic philosophy. He said we can and must distinguish between nature and grace. What he meant was, there are certain things we can learn from nature that we don't learn from special revelation. The bible doesn't teach us anything about nuclear physics, or molecular biology, even though the study of these things is made possible by the common grace of God on man. And while these things are to be distinguished, one cannot be true in one arena and false in the other. This would violate the law of non-contradiction.

Thomas added a third category- the articulus mixtus (mixed articles). These are things that can be learned from either the Bible or from the study of nature. Chief among these things is the existence of God (RE Paul in Romans 1). Thus, the reason the Bible does not argue the existence of God is, from the beginning, God has proven his existence beyond any doubt in nature. So Aquinas argues that the existence of God is proven both by nature and by scripture. He doesn't separate these two things, he makes distinctions.

Thomas stood on Augustine's shoulders. Augustine taught his students that they should learn as much as they could learn about whatever they could, because all truth was God's truth and would reveal God. Augustine's natural theology was based on Paul, of course.

In Rom. 1, Paul goes back to show why the gospel is necessary, and this is based in general revelation. People aren't condemned because of rejecting the Jesus they've never heard of, but because of what they've done with the knowledge of God that they DO have. This 'suppression of the truth of God' is the primary sin of fallen humanity. As Paul says, God has made the truth about himself (that may be known) manifest (phaneros/manifestum); yet we have rejected it.

The general revelation Paul speaks of produces a natural theology in us. This natural theology clearly gives us enough knowledge to condemn us. It does not give enough to save us. For that we need special revelation.

One other point is important: If God reveals himself in nature and in scripture, and the primary textbook of the scientist is nature, and the primary textbook of the theologian is the Bible, why is there conflict between science and theology? Because we live in a fallen world, we don't have complete understanding of either nature or God. Both the scientific community can correct the church (as we probed earlier in the term), and the church can correct the scientific community. But both nature and scripture reveal God, limited as our understanding in both arenas may be.

Reference- Sproul RC. Defending your faith.

06 April 2011

A Good Reason to NEVER Share the Gospel With Anyone

I've been reading blog posts and articles in the last few weeks that are hit-and-miss around the topic of hell, all brought on by the Rob Bell book, of course. Reading the comments in many of the blogs has convinced me of two things:

(1) There's a LOT of bad theology walking around out there, and

(2) Many people can't seem to see the logical inconsistency in the propositions they say they uphold

One of the most striking has been the idea that God will not hold anyone who has not heard the gospel accountable for their sin. I won't go into a long theological treatise here, but say this-

In fact, let's defund all the missionaries and bring them home. We have whole countries (yea, continents) that haven't heard the gospel yet...how about we just don't tell them so they won't be accountable for their sin? If we could bury all the bibles in the world and shut down all the churches, and make it illegal to share the gospel, then we could all safely become universalists, because with no one hearing the good news, everyone would wind up in paradise, no?

Sorry to sound crass, but demonstrating the illogic of those peoples' position requires it, I think.

(1) There's a LOT of bad theology walking around out there, and

(2) Many people can't seem to see the logical inconsistency in the propositions they say they uphold

One of the most striking has been the idea that God will not hold anyone who has not heard the gospel accountable for their sin. I won't go into a long theological treatise here, but say this-

If you really believe that God won't hold people who have never heard the gospel accountable for their sin, then you should NEVER UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES share the gospel with anyone, lest they reject it and wind up in hell.

In fact, let's defund all the missionaries and bring them home. We have whole countries (yea, continents) that haven't heard the gospel yet...how about we just don't tell them so they won't be accountable for their sin? If we could bury all the bibles in the world and shut down all the churches, and make it illegal to share the gospel, then we could all safely become universalists, because with no one hearing the good news, everyone would wind up in paradise, no?

Sorry to sound crass, but demonstrating the illogic of those peoples' position requires it, I think.

11 March 2011

Update on the Hell Issue (Or, One Hell of an Update)

After I posted my note a couple days ago, Al Mohler posted a two-part series on the controversy.

Here's part one.

Here's part two.

R. C. Sproul, Jr., added this interesting article called, Can a Person Be Evangelical and Not Believe in Hell?

Then Justin Taylor added this excerpt and description called, Rob Bell on Martin Luther and Salvation in Hell. (Bell claims Luther believed one could be saved from hell after death.)

Finally, we have a review of the book itself (still not released yet) via a pre-release PDF version granted for review purposes. One of the most talented Christian book reviewers around has done that review for us.

Here's Tim Challies' review of Bell's book, Love Wins.

Here's part one.

Here's part two.

R. C. Sproul, Jr., added this interesting article called, Can a Person Be Evangelical and Not Believe in Hell?

Then Justin Taylor added this excerpt and description called, Rob Bell on Martin Luther and Salvation in Hell. (Bell claims Luther believed one could be saved from hell after death.)

Finally, we have a review of the book itself (still not released yet) via a pre-release PDF version granted for review purposes. One of the most talented Christian book reviewers around has done that review for us.

Here's Tim Challies' review of Bell's book, Love Wins.

07 March 2011

What the Heck is the Fuss About Hell?

If you follow the Christian blogosphere at all, you've seen a lot of traffic lately about the idea of the reality of Hell. (No, not the place Cubs fans live every year in October, but the place in the Bible.)

It was all generated by media releases on Rob Bell's new book that's coming out...one in which (according to the media push) he reveals himself to be a universalist. (Ironic what 'Bell' rhymes with...).

What's a universalist? Universalism is the theological position that claims everyone will end up in heaven after all is said and done. There are some creative ways to get there, but either now, later, or really later, everyone gets to paradise.

Can a believer be a universalist? I don't think so. Tim Challies posted this thoughtful blog entry this morning, and he says things more succinctly and thoughtfully than I usually do, so I'll point you to his post for the summary of why one can't be a universalist and a believer (at least, the way I think 'believer' is to be defined) at the same time.

Why do I believe in a literal hell? The primary reason I believe in a literal hell is that Jesus did. I haven't physically counted the references, but I've read in several places that claim Jesus mentioned hell more often than he mentioned heaven in the gospels in the New Testament. That seems to mean it is an important concept. If you look at the story of the rich man and Lazarus, you can't but clearly see Jesus thought of hell as a physical reality.

Isn't it unlike a loving God to condemn people to hell for eternity? This one's been around a long time, and still is (I've read it on blog comments just this week). Those who think this way are imposing a humanistic form of fairness on God. They understand neither the holiness of God nor the sinfulness of man; or for that matter, the ugliness of our sin before that holy God. I always recommend a particular book to them: The Holiness of God by R. C. Sproul. It makes as clear and concise a biblical statement on these issues as I think anyone has ever made in print.

So why do people deny a literal hell? In some ways, that question is hard to answer. On the one hand, I myself wish hell wasn't a real place...contemplating people who I'm pretty sure have gone or are going there is unsettling at best. On the other hand, there are certain people who seem to deserve it (Hitler and the usual suspects). But I have to constantly remember that the thing that separates me from Hitler in terms of deserving hell or heaven has nothing to do with the deaths of 20 million (plus) people. It has to do with the fact that I'm a sinner, just like he was; but I am a sinner saved by grace. I have no evidence he was. I don't know of anyone who does have that evidence.

I suppose the biggest reason people deny the existence of hell relates to my first idea...it is too terrible to contemplate. But not being thinkable doesn't make it go out of existence. The idea that Jesus would die on a cross for someone like me is too hard to contemplate as well, but it happened. That's the nature of God's grace. But for there to be anything called 'grace' at all, there has to be something called 'justice'.

The great irony of time is that the moment in history where God's grace is seen the clearest, at the cross, is also the moment in time where God's justice is seen in all its power the clearest. Grace and mercy come together with justice and wrath at the cross. Wow.

It was all generated by media releases on Rob Bell's new book that's coming out...one in which (according to the media push) he reveals himself to be a universalist. (Ironic what 'Bell' rhymes with...).

What's a universalist? Universalism is the theological position that claims everyone will end up in heaven after all is said and done. There are some creative ways to get there, but either now, later, or really later, everyone gets to paradise.

Can a believer be a universalist? I don't think so. Tim Challies posted this thoughtful blog entry this morning, and he says things more succinctly and thoughtfully than I usually do, so I'll point you to his post for the summary of why one can't be a universalist and a believer (at least, the way I think 'believer' is to be defined) at the same time.

Why do I believe in a literal hell? The primary reason I believe in a literal hell is that Jesus did. I haven't physically counted the references, but I've read in several places that claim Jesus mentioned hell more often than he mentioned heaven in the gospels in the New Testament. That seems to mean it is an important concept. If you look at the story of the rich man and Lazarus, you can't but clearly see Jesus thought of hell as a physical reality.

Isn't it unlike a loving God to condemn people to hell for eternity? This one's been around a long time, and still is (I've read it on blog comments just this week). Those who think this way are imposing a humanistic form of fairness on God. They understand neither the holiness of God nor the sinfulness of man; or for that matter, the ugliness of our sin before that holy God. I always recommend a particular book to them: The Holiness of God by R. C. Sproul. It makes as clear and concise a biblical statement on these issues as I think anyone has ever made in print.

So why do people deny a literal hell? In some ways, that question is hard to answer. On the one hand, I myself wish hell wasn't a real place...contemplating people who I'm pretty sure have gone or are going there is unsettling at best. On the other hand, there are certain people who seem to deserve it (Hitler and the usual suspects). But I have to constantly remember that the thing that separates me from Hitler in terms of deserving hell or heaven has nothing to do with the deaths of 20 million (plus) people. It has to do with the fact that I'm a sinner, just like he was; but I am a sinner saved by grace. I have no evidence he was. I don't know of anyone who does have that evidence.

I suppose the biggest reason people deny the existence of hell relates to my first idea...it is too terrible to contemplate. But not being thinkable doesn't make it go out of existence. The idea that Jesus would die on a cross for someone like me is too hard to contemplate as well, but it happened. That's the nature of God's grace. But for there to be anything called 'grace' at all, there has to be something called 'justice'.

The great irony of time is that the moment in history where God's grace is seen the clearest, at the cross, is also the moment in time where God's justice is seen in all its power the clearest. Grace and mercy come together with justice and wrath at the cross. Wow.

28 February 2011

Taking a Class

As a professor and dean, the idea of taking a college class is kinda scary...it's like the jailer getting thrown in jail, or something like that. Anyway, I was asked a question a few weeks back in my Sunday School class, and I wasn't able to answer it cogently. I don't like that feeling.

So I signed up for RLGN 5325 Historical Theology here at Wayland. Now I'm in an online class full of theology students. It's a bit intimidating for someone trained as a scientist. But I need the background of historical theology to answer those, "Why do we do the things we do" questions, and I'm also thinking the course will both strengthen my faith and teach me a bit more about the nature and character of God in the process. Obviously, those are worthwhile reasons to take the course.

I'm probably nuts, but I'm going to do it anyway.

So I signed up for RLGN 5325 Historical Theology here at Wayland. Now I'm in an online class full of theology students. It's a bit intimidating for someone trained as a scientist. But I need the background of historical theology to answer those, "Why do we do the things we do" questions, and I'm also thinking the course will both strengthen my faith and teach me a bit more about the nature and character of God in the process. Obviously, those are worthwhile reasons to take the course.

I'm probably nuts, but I'm going to do it anyway.

01 February 2011

Do We Get Our Theology from Kindergarten?

It is well-known that much of American evangelicalism holds the idea that if God provides some form of grace (say, salvation) to one person, he is really obliged to provide it equally to everybody. That's not a biblical concept (Rom. 9:15, for example), but it is still widely held in society. Where did it come from?

Maybe our kindergarten teachers taught it to us. You remember the little book that was popular back in the 90s, called, Everything I Needed to Know, I Learned in Kindergarten? I thought the book was a dumb idea then, because it isn't true, and if it contributed to our theological mess, I think it is even dumber now than I did then. It was cute, but still dumb.

Pretty much everyone I know has had some form of this experience- "I brought a piece of candy to school...the teacher saw it and said, 'If you don't have enough of those for everybody, you can't have any either!' So I put it away (or had it confiscated)." Is that where we got this misguided idea about God?

R. C. Sproul, in his classic book, The Holiness of God, addresses it this way-

It is impossible for anyone, anywhere, anytime to deserve grace. Grace by definition is undeserved. As soon as we talk about deserving something, we are no longer talking about grace; we are talking about justice. Only justice can be deserved. God is never obligated to be merciful. Mercy and grace must be voluntary or they are no longer mercy and grace. God never “owes” grace. He reminds us more than once. “I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy.” This is the divine prerogative. God reserves for Himself the supreme right of executive clemency.

Suppose ten people sin and sin equally. Suppose God punishes five of them and is merciful to the other five. Is this injustice? No! In this situation five people get justice and five get mercy. No one gets injustice. What we tend to assume is this: If God is merciful to five He must be equally merciful to the other five. Why? He is never obligated to be merciful. If He is merciful to nine of the ten, the tenth cannot complain that he is a victim of injustice. God never owes mercy. God is not obliged to treat all men equally. Maybe I’d better say that again. God is never obliged to treat all men equally. If He were ever unjust to us, we would have reason to complain. But simply because He grants mercy to my neighbor gives me no claim on His mercy. Again we must remember that mercy is always voluntary. “I will have mercy upon whom I will have mercy.” (p. 128-9)

By the way, if we are indeed getting some of our ideas about God from secular schooling and the control of interpersonal behavior therein, that does not paint a pretty picture of theological education in our churches.

Get this book by Sproul. If you live near me, ask me and I'll give you a copy. It's worth the read.

Maybe our kindergarten teachers taught it to us. You remember the little book that was popular back in the 90s, called, Everything I Needed to Know, I Learned in Kindergarten? I thought the book was a dumb idea then, because it isn't true, and if it contributed to our theological mess, I think it is even dumber now than I did then. It was cute, but still dumb.

Pretty much everyone I know has had some form of this experience- "I brought a piece of candy to school...the teacher saw it and said, 'If you don't have enough of those for everybody, you can't have any either!' So I put it away (or had it confiscated)." Is that where we got this misguided idea about God?

R. C. Sproul, in his classic book, The Holiness of God, addresses it this way-

It is impossible for anyone, anywhere, anytime to deserve grace. Grace by definition is undeserved. As soon as we talk about deserving something, we are no longer talking about grace; we are talking about justice. Only justice can be deserved. God is never obligated to be merciful. Mercy and grace must be voluntary or they are no longer mercy and grace. God never “owes” grace. He reminds us more than once. “I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy.” This is the divine prerogative. God reserves for Himself the supreme right of executive clemency.

Suppose ten people sin and sin equally. Suppose God punishes five of them and is merciful to the other five. Is this injustice? No! In this situation five people get justice and five get mercy. No one gets injustice. What we tend to assume is this: If God is merciful to five He must be equally merciful to the other five. Why? He is never obligated to be merciful. If He is merciful to nine of the ten, the tenth cannot complain that he is a victim of injustice. God never owes mercy. God is not obliged to treat all men equally. Maybe I’d better say that again. God is never obliged to treat all men equally. If He were ever unjust to us, we would have reason to complain. But simply because He grants mercy to my neighbor gives me no claim on His mercy. Again we must remember that mercy is always voluntary. “I will have mercy upon whom I will have mercy.” (p. 128-9)

By the way, if we are indeed getting some of our ideas about God from secular schooling and the control of interpersonal behavior therein, that does not paint a pretty picture of theological education in our churches.

Get this book by Sproul. If you live near me, ask me and I'll give you a copy. It's worth the read.

26 January 2011

Horton's, "The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology"

I just got my copy of Mike Horton's new systematic theology. It is MUCH bigger in the hand than it looks in the amazon.com photo.

I've been waiting on this for a while. I have used Grudem for years, and still love it and recommend it. (I don't know of any systematic theology more accessible to the layperson than Grudem.) There are, however, a few areas of Grudem I don't like as much, and I'm curious to see how differently Horton treats them. (I think Grudem flirts with old-earth creationism a bit too much, and I tend to be a bit more cessationist than Grudem is, for a couple of examples.)

I'll post a review of this book down the road. Probably way down the road, as systematic theologies tend not to be page-turners at times, and this one is right at a thousand pages long.

I've been waiting on this for a while. I have used Grudem for years, and still love it and recommend it. (I don't know of any systematic theology more accessible to the layperson than Grudem.) There are, however, a few areas of Grudem I don't like as much, and I'm curious to see how differently Horton treats them. (I think Grudem flirts with old-earth creationism a bit too much, and I tend to be a bit more cessationist than Grudem is, for a couple of examples.)

I'll post a review of this book down the road. Probably way down the road, as systematic theologies tend not to be page-turners at times, and this one is right at a thousand pages long.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)